- Home

- Susan Wooldridge

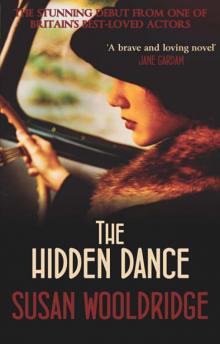

The Hidden Dance

The Hidden Dance Read online

The Hidden Dance

Susan Wooldridge

First published in Great Britain in 2009 by

Allison & Busby Limited

13 Charlotte Mews

London W1T 4EJ

www.allisonandbusby.com

Copyright © 2009 by Susan Wooldridge

The moral right of the author has been asserted.

Extract on page 307 from The House at Pooh Corner by A.A. Milne © The Trustees of the Pooh Properties. Published by Egmont UK Ltd, London, and used with permission.

All characters and events in this publication, other than those clearly in the public domain, are fictitious and any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, is purely coincidental.

This book is sold subject to the conditions that it shall not, by way of trade or otherwise, be lent, resold, hired out or otherwise circulated without the publisher’s prior written consent in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition being imposed upon the subsequent purchaser.

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

ISBN 978-0-7490-0763-8

Digital conversion by Pindar NZ

For Andy, without whom this book couldn’t have been written.

Prologue

Clear as clear she hears whispers from behind the half-open door.

‘Wait, the hat’s not straight. Now!’

With hands obediently over her eyes, she glimpses the drawing-room door swing wide and a small pair of feet comes pattering in.

‘Now, Mummy, now. Open your eyes!’

Clear as clear she sees… A little clown. White pointy hat, red pom-poms the size of dahlias, baggy white suit, a gleaming face. Up to this point the memory is perfect. But a new voice, a man’s voice, spoils it all and she freezes. Even in the memory.

‘Stop hiding behind closed doors.’

Mother and child stand very still. The man arrives in the doorway. She moves in front of the child to shield him.

The man speaks. Quietly. Almost a whisper. Seductive. ‘You can’t seriously be thinking of dressing the boy like that.’

She tucks her hand behind to the boy. He clutches it.

The man turns to leave the room.

She cries out without thinking, ‘But it’s his party—’

She stops. The man is turning back.

‘Get those clothes off him,’ he whispers. ‘I won’t say it again.’

The boy runs. The door slams.

The man roars after him, ‘Nicholas!’ Then he turns slowly back to her. ‘You bitch! My God, you’ll pay for this!’

Her cry is cut off by the first slap, the sound cracking through the stillness of the day. She gasps, winded. Tries to keep the terror from her face, doesn’t want to anger him further.

He stands swaying slightly. She struggles for breath and sees his hand swing back a second time. ‘Oh no! Please, don’t—’

He delivers the second slap to the side of her head, catching her ear. The pain is precise, crystal clear. All is silent except for the ringing, singing pain – and a far-away knocking.

‘My lady, my lady, open the door! Oh, my lady!’

The man leans over her, slowly raising his hand. He doesn’t strike. ‘Get rid of her!’

She opens the door.

Her maid’s face is white, tears in her eyes.

‘Go away, Mary. Please!’

From behind, the man shoves her and slams the door shut.

‘You’ve made the child a pansy-boy!’ She feels the spray of his spit on her face, smells the drink on his breath.

He pushes her to the ground.

‘You revolt me!’ There is extraordinary loathing in his voice.

He leaves, banging across the hall, slamming the front door.

She lies still, huddled on the carpet, ashamed, terrified at the enormous anger she has provoked.

Everything is quiet.

Part One

Chapter One

SS Etoile. Friday morning, 3rd March 1933

Across the third-class day room the children tore back and forth, skipping and hopping, thrilled with their new outfits of limp velvet and torn taffeta. As she watched them, Lily thought, It’s the smell of camphor that’s always so extraordinarily intoxicating.

Mothballs and camphor, the scent of dressing up.

Into her mind came Nickie and clearly she saw her son, her darling Nicholas – the only child she really wanted to see playing and dressing up. Her darling boy, dressed as a little clown. How happily he would have joined in with these children here, she thought. These children who play so freely. How he would have loved to dress up with them…

As she sat on the ship crossing the Atlantic, such a long time since Nickie’s Pierrot fancy-dress party, Lily suddenly felt overwhelmingly sick, her imagination painting pictures that left her trembling. Always the memory of him dressed as a little clown brought a fear that grew and grew and flooded her entire being.

Enough. She turned away from the children.

Slowly the nausea ebbed.

She stretched. She’d been momentarily distracted by the bustle created by the arrival of two huge wicker dressing-up baskets. She’d attempted to focus on a large woman, a tumble of skirts and shawl, at the centre of the room, trying to tempt a pale plump little girl into a frowzy frock and bonnet. Dear Lord, what a dreadfully unappealing child – what must its mother feed it on? Mind, the fat woman herself can hardly move.

She turned away. These thoughts didn’t hold her; she was too restless to concentrate. Since the previous evening a storm had been threatening. Ropes had been rigged to imprison wooden benches and trestle tables; tablecloths dampened to hold sliding cutlery and tea-urns. But the storm had not arrived. Now a trio of sailors on the edge of the large communal room stood ravelling up the storm ropes, skillfully flipping and coiling them to avoid the excited children, all pulling out shirts, skirts, bonnets and caps from the big old baskets. Through the portholes, Lily saw the lumpy clouds unroll and slip away, and the weather, as if to apologise for its former bad behaviour, suddenly beamed bright and clear, the sunlight dancing through the swirls of dust that heralded each newly discovered costume.

She felt removed and out of place in this sea of clatter and banter, and having chosen a bench in the far corner, she clung here to the vestiges of quiet. All she wanted was to be left in peace, to be completely unnoticed. Leaning back against the wall, she closed her eyes. Her apricot hair, she knew, caught attention, but for this trip she’d decided to keep her so-called crowning glory discreetly hidden, the curling waves pulled back into a bun of puritan severity. Nothing otherwise, she prayed, distinguishes me. I’m just a tired middle-aged woman in an old tweed skirt and beige cardigan.

She stared down at the acres of dreary linoleum upon which so many feet were drumming, drumming…and caught sight of her shoes. Chocolate suede lace-ups with a small heel. They were old but expensive and hand-made, thin leather ties neatly threading through the eyelets, and in some ways the shoes were even more elegant in their battered state. All her maid’s clothes had fitted her, the tweed skirt and the coat, Mary’s dusty-pink crepe blouse – a bit on the big size but better that than the other way around. No, it was Lily’s large feet that had let her down; she’d had to resort to an old pair of her own shoes. Mr Mancini’s – and she suddenly had an image of her wooden lasts lined up with dozens of others in the backroom of the smart shoe shop in Bruton Street. So, so far away.

Perhaps, she thought, they are the one item that will give me away: my shoes. Some eagle-

eyed snooper will catch sight of them and, putting two and two together, report me to the captain. She tucked her feet hastily under the bench as the absurd thought made her heart beat irrationally, a sudden skim of sweat breaking out on her forehead. She pulled her hanky from her sleeve, held it to her brow and, making herself breathe evenly, stared on, unseeing, at the sallow green linoleum.

Three days at sea and already the trip seemed interminable. Oh, how she longed for the hush of first class high above her. Down here, the constant mayhem was proving such a terrible torment after the many sleepless nights that had preceded her trip. Though she had to admit, steerage was not quite as tiresome as she’d feared. Having always hitherto travelled first class, she’d wandered through the third-class smoking rooms and day rooms, surprised to find them open and spacious.

No, it was the cabin itself that was proving such a trial. Not that the spartan berth was uncomfortable, just so tiny. And always the endless heavy churning of the engines making any sleep or rest impossible, so that however much she longed to be away from these rowdy crowds and their endlessly drumming feet, the claustrophobia of her cabin was, today, much worse than this boisterous chaos. She had survived two days cooped up but the need for space and distraction had driven her into this, the third-class day room.

And then, as if in answer to her prayers, the noise in the large room fell into a lull and the most wonderful peace descended. With a sigh of relief, Lily stirred herself upright and turned with resolve to the journal on her lap. But the relief was short-lived for all at once there started into life the whine and hum of a pair of bagpipes.

Oh Lord, this is too much – it must be stopped! She spun round.

Instantly any word of complaint died on her lips. Beside her, hitherto unnoticed, sat a group of people tightly huddled round a table, concentrating on the whining noise spooling from a hidden centre. As the pipes warmed up, the huddle uncoiled, revealing a dozen people, their faces gnarled and tanned; citizens of a far-away life. At their heart sat a large square blond man swathed in a tartan shawl. The player of the bagpipes, chief of his tribe, his cheeks were full-blown as he massaged the bag of sound.

A whoop, a cheer, clapping hands.

Lily stared, caught by the unexpected sight and sound, the chief’s muscular hands drawing forth the trembling haunted music of mountains. Now, from the midst of the shawled group, an old woman rose up and, cupping a hand to her ear, turned her tanned beaten face to the ceiling and started to ululate the meandering cry of minarets. The mystical sound coiled round and round the room. On and on. Lily sat entwined.

‘You like our music, lady?’

The music had stopped and, on a whine, the swollen bag was deflating.

‘You smile, you like our music?’

Lily, stung into life, found the blond man looking straight at her. Expecting a Scottish voice to go with the bagpipes, she was instantly thrown into confusion – not so much by the man’s rough incomprehensible accent but by his jet-black eyes, glittering, full of life… She scrabbled for something to say, unsettled by the sensual power of his gaze.

‘I beg your pardon?’ (Oh heavens, I sound such a stuck-up fool!)

Unable to think of anything more, she was left smiling helplessly like a child as, around their chief, the women chirruped a spiral of chattering sounds. Perhaps from the Balkans, she thought, all their dark eyes now upon her.

‘Our music, lady. You like?’

He held the tangle of pipes high above his head. Trusting the pipes were the subject under discussion, she nodded eagerly. ‘Very good.’ With a faltering smile, all she could muster under the circumstances, she lifted her hands, gesturing a clapping motion, childishly eager to please these new acquaintances.

The shawled heads of the women danced and bowed in gusts of laughter and, in her confusion, Lily found herself laughing along as well. Then, just as suddenly, their attention left her. With much relief, she realised she no longer held any interest for them; the man had started singing and all eyes turned in on him once more.

Agitated, she glanced to and fro to see who had witnessed this embarrassing interlude and her subsequent abandonment. Then the fear caught her again. Had she been seen? Had someone glanced across, alerted by the music, and recognised her sitting there, so that even now a purser was being told of her presence on board? She tentatively scanned the vast room.

But no one was looking at her; no one was in the least bit interested. She was alone again.

In the middle of the vast room, Mrs Webb’s spirits were seriously flagging. Having polished off cock-a-leekie soup, a couple of grilled mutton chops and apple meringue for her midday meal, all the large woman really wanted was a nice little nap on the comfy bunk in her cabin. But ever game – especially under testing circumstances (that apple pudding was sitting very heavy) – Mrs Webb rallied herself. ‘Keep going, lass, this boat trip’s nearest thing to ’oliday that family’s gonna get.’

And, everything considered, she had to admit it was turning out to be a right good ‘do’ – fresh air, free food a-plenty, a champion tug-of-war on deck that morning and tomorrow’s fancy-dress parade to look forward to.

She felt a feeble tug at her skirts and looked down. ‘I’ll not tell thee again, our Anthea,’ she snapped, ‘stop thy pulling.’

‘But I’m tired, Gran,’ wheedled the child, her pasty face hidden by a fat little fist, the thumb buried deep in her mouth. ‘I want to go ’ome.’ The thumb popped out and popped in again. The child was dressed in a faded lemon-yellow cotton dress. Once her best – it had been smocked by Mrs Webb herself – it now strained tight over the puffy little girl, its colour sour and unforgiving.

Mrs Webb chose to ignore her grandchild. She knew Anthea wanted nothing to do with any fancy-dress competition but she was determined not to let the child slump into yet another sulky fit. Aye but to that end, she feared, it’d take a deal more than fresh air and free food.

‘Get cracking, me duck,’ she admonished, gesturing towards the big old wicker baskets, ‘else all big boys and girls’ll take best fancy dress.’ And wiping her face with a sparkling white handkerchief the size of a picnic cloth, she sank gratefully onto a large wooden chair that creaked loudly as it received her.

‘Gran?’

Mrs Webb looked down. The little girl was holding up a battered straw bonnet trailing a mould-spotted ribbon.

‘Go on, me lovely, that’ll be Bo-Peep.’

‘But Gran—’

‘Come on now, let’s see what else we can find.’

Aware that all Anthea wanted was to run away and hide every inch of her wobbly body, as the two of them searched through the mounds of musty material, Mrs Webb tried to shield the child from view by means of her own corpulence.

Ten years old and she should be such a pretty little girl, she thought. Her mam was right bonny at that age. And, of course, Mrs Webb knew that that was the real reason for the child’s despair – five empty years without her mother. Poor little mite, no wonder the girl was sullen and fractious; her mam’s shocking death was enough to smack away any child’s pep and charm. No, little Anthea had never really had a chance.

‘Gran, where’s me sheep?’ asked the child in a tiny voice and, sinking onto the floor, tears very near, she sat utterly defeated by her struggle to become a shepherdess.

Her grandmother looked at the miserable girl. A new start’s what this child needs if she’s to survive: a new start to make her forget. Make us all forget.

‘Nay, lass, you’re right,’ she said, shaking her head. ‘It won’t do, it won’t do a’ all.’

And never one to be brought down by Fate’s travails, the large woman levered herself back onto her feet and started to rummage in the wicker basket as though her life depended on it.

Ten years later, sitting in a garden, Anthea would say, ‘And that was the beginning, that day on the boat. The beginning of what I can remember of my life. I’d been asleep, like, since my mam’d died, five years before, and I

couldn’t remember anything – still can’t, not from those five years. And then that day on the boat, I woke up – I s’pose from when me and Gran met you. It was the start of the adventure. And now I have memories. From our trip all together.’

And Lily had smiled.

Lily looked down at her journal. At the top of the page she had written the day’s date. Friday, 3rd March 1933. But besides that, what was there to write after all?

She screwed up her eyes in an effort to drown out the screams and the endless banging noise of the children, and tried to compose her thoughts. At her side her neighbour’s insistent singing vied with the whirl of childish cries. She put pen to paper.

Nothing appeared; her fountain pen had dried up.

For heaven’s sake. Lily shook it. Still nothing. She tried the little lever on the side only to be rewarded by a large inky blob swelling from the nib, which hovered over the snowy-white page and then firmly plopped onto her tweed skirt.

‘Oh no, this wretched pen.’

‘A tomato’s what you need for that.’

Surprised not only by the proximity of the voice but also at the eccentricity of the suggestion, Lily swung round to find the large dressing-up woman at her elbow. If she had hoped to make a reply of some kind, it was now washed aside in a torrent of advice from the large woman, who settled herself comfortably on the bench next to her.

‘A tomato. Rub it well into the wet ink-mark then rinse it out wi’ water. Never fails. Mind, they say if you put red ink over black ink, it dissolves the iron in your black ink so that when you wash it, it’s gone – t’ stain, I mean. But I don’t think it’s as – efficacious.’ Lily caught the echo of an ‘h’ before the word. ‘Anyway, love, where we gonna find red ink down ’ere?’

The Hidden Dance

The Hidden Dance